Is Your PFAS Data FAIR?

How PDFs and missing qualifiers keep “insufficient data” on repeat

It’s 2026 and “data availability” is no longer the constraint people pretend it is. We see datasets everywhere: in PDFs attached to regulatory comments, in lab reports exported from LIMS, in product listings, in public dashboards, in supplementary tables that are technically downloadable but practically unusable.

The constraint is whether any of that information can be trusted, joined, and defended once it leaves the room it was created in.

That is why when we talked last week about the FDA’s PFAS-in-cosmetics report is such a useful frame. The headline was “insufficient data,” but the deeper lesson is that our systems still struggle to translate ingredient presence into defensible conclusions about exposure, fate, and risk. The report also exposes something many of us have learned the hard way, which is even chemical identity is fragile when it is handled as text. The FDA notes, for example, that polyvinylidene fluoride was not retrieved by their search and had to be added after confirmation in the wINCI database. That is not an embarrassing footnote. It is the whole problem in miniature.

So yes, an expanded article on FAIR data is not a detour, but it’s the missing engineering layer beneath “insufficient data.”

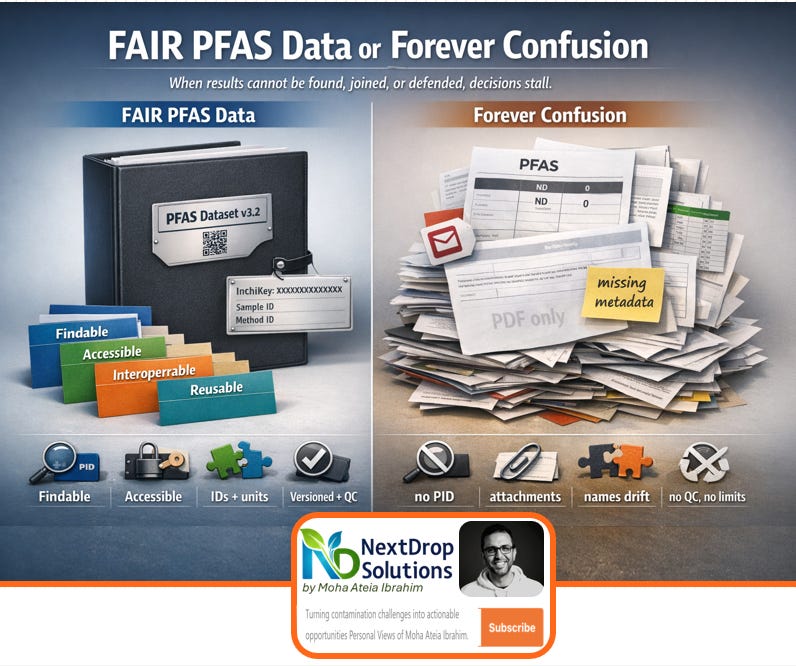

FAIR, for readers who have only heard it as a slogan, is not a call for everything to be open. It is a set of design constraints for data stewardship: Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable. The principles were formalized in 2016 by Wilkinson and colleagues, with an explicit emphasis on machine actionability, not just human readability. The real point is blunt. If data cannot move cleanly across people, labs, software, and time, it cannot support decisions at scale.

And PFAS is the stress test.

In PFAS work, we routinely ask questions that cannot be answered by any single dataset. Utilities want to connect influent signatures to upstream sources. Regulators want to compare monitoring results across jurisdictions and methods. Researchers want to map suspect screening hits to structures, functions, and toxicity. Industry wants to understand where a substitution reduces risk rather than just changing the name on a label. All of this requires joining disparate data objects. Most of our current reporting practices make that join unnecessarily difficult.

The most common failure mode is identity. Names drift. CAS numbers are missing or wrong. Polymers, mixtures, and salts complicate everything. When identity is managed as a string field in a table, the best case is wasted time. The worst case is a wrong conclusion that looks rigorous because it has a lot of numbers.

This is exactly why structure-based identifiers matter. InChI and InChIKey were designed as non-proprietary, machine-readable representations of chemical structures to enable linking across data sources. EPA’s CompTox Chemicals Dashboard and DSSTox infrastructure are practical examples of what this looks like in an applied regulatory context, with unique structure-linked identifiers (DTXCIDs/DTXSIDs) that can be used for batch searches and mapping. You do not need to love any particular database to accept the core lesson that PFAS data that cannot be reliably mapped to structure is not interoperable, and therefore not reusable.

The second failure mode is metadata, especially around censoring and QA. Environmental PFAS datasets are full of “non-detects,” but too many tables still present them as blanks or zeros without reporting detection limits, reporting limits, qualifier logic, or blank handling. That is not a statistical nuance. It changes load estimates, trend interpretation, and risk communication. When a consultant tries to reconcile two datasets and cannot tell whether “ND” means below method detection limit, below reporting limit, or simply not analyzed, the dataset is not reusable in any defensible way.

The third failure mode is method dependency, and it is getting harder as the field shifts from targeted analysis to suspect screening and non-targeted workflows. If you want one contemporary reminder that “PFAS detected” is not a universal statement, read NIST’s PFAS non-targeted analysis interlaboratory study. It is a controlled comparison of LC-HRMS identification performance across laboratories, built specifically to illuminate interlaboratory variability and reporting dependencies. The message for practitioners is simple. If spectra, libraries, scoring logic, and confidence criteria are not reported in a structured way, downstream users cannot reliably interpret, compare, or reuse the output.

This is where the “FAIR or forever confusion” tension becomes real. We are entering a policy moment that will dramatically increase the amount of data that is publicly accessible, without guaranteeing it is reusable. The 2022 OSTP memo directed federal agencies to update public access policies by December 31, 2025, to make publications and supporting data publicly accessible without embargo, while still recognizing the need to protect confidentiality, privacy, and business confidential information. That is a major shift. But “public access” does not automatically produce interoperability. In the PFAS space, it can easily produce a larger haystack.

If that sounds harsh, consider how often the industry and regulatory conversation gets stuck on counts, not flows. The FDA cosmetics work quantified presence in registered products and then ran into data gaps on toxicology and exposure parameters. Meanwhile, the academic literature is trying to fill in pieces of the exposure story. These are not competing narratives, but complementary pieces of a system that only becomes legible when the data can be joined.

FAIR, applied to PFAS, is how you turn those pieces into something decision-grade.

In practice, the most important shift is to stop treating FAIR as an abstract virtue and start treating it as a deliverable specification. Any one working in this space, knows how extremely expensive and exhaustive the PFAS analysis and data generation. That’s why I think efforts on more data management need to be imperative, not just “accessible” requirement by some agencies. PFAS dataset should be findable beyond a DOI, meaning it is indexed with persistent identifiers and a clear version. It should be accessible in the sense that it can be retrieved by humans and machines, even if access is controlled. It should be interoperable, meaning it uses stable identifiers for chemicals, matrices, methods, and units, and it encodes qualifiers rather than hiding them in footnotes. It should be reusable, meaning it carries enough provenance, QC context, and censoring detail that someone else can reanalyze it without reverse-engineering your intentions.

The encouraging news is that the environmental community already has working examples of this mentality. The NORMAN Suspect List Exchange is explicitly framed as an open, FAIR platform for suspect screening lists, with versioning and citable records through Zenodo so that users can reference specific list versions rather than an evolving blob. That is exactly the model we need more widely. We need curated lists and datasets that are trackable, linkable, and designed for integration.

The hard part is governance, not software. Utilities are right to worry about data being weaponized out of context. Industry is right to worry about confidential formulations. Regulators are right to worry about burden and enforceability. FAIR does not require that every raw file be public. FAIR requires that the data objects be structured so they can be found, interpreted, and reused under appropriate access conditions. The OSTP memo itself explicitly recognizes the need to protect confidentiality and business confidential information while expanding access. The opportunity is to separate “what must be shareable” from “what must be protected,” without sacrificing interoperability.

So what should change, concretely, for practice?

For researchers, journals, and reviewers, the baseline should be that every quantitative PFAS table is released in a machine-readable format with explicit units, detection and reporting limits, qualifier logic, blank handling, and a data dictionary. If structures are known, include structure-based identifiers, not just names. If suspect or non-targeted workflows are used, report libraries, versions, scoring logic, and confidence levels in a structured way. The standard is not “can a reader follow this,” it is “can another competent group reuse this without guessing.”

For regulators and program managers, the next step is to move away from narrative reporting expectations and toward structured templates that make interoperability a default. OECD Harmonised Templates exist precisely to standardize reporting for chemical properties, effects, uses, and exposure contexts, and they can serve as specifications for data management systems like IUCLID. EPA’s work on harmonized templates for research data is pointing in the same direction, recognizing that decision relevance depends on consistent reporting structure.

For utilities and consultants, the most immediate action is procurement discipline. Stop accepting “data dumps” as final deliverables. Require consistent identifiers, data dictionaries, and version control. Require explicit reporting-limit metadata and censoring conventions. Require sample and method metadata that can survive staff turnover and contractor changes. In a litigation-aware PFAS environment, this is risk management.

If we do this well, “insufficient data” becomes a narrower, more honest phrase. It will mean genuinely missing toxicology or genuinely missing exposure parameters, not “we have numbers but we cannot use them.”

If we do not, we will get the worst of both worlds moving forward with more public data, more dashboards, more arguments, and surprisingly little additional decision clarity.

Great read! Thank you for writing.

Thanks for this article!