Are We Brave Enough to Pay the 'Pivot Penalty'?

Science has long rewarded deep specialization. But as global challenges grow more complex, are we penalizing the very adaptability needed for breakthrough solutions?

Hey everyone, Moha here, Unfiltered as always ;)

There’s a certain romance to the image of a scientist, isn’t there? The lone wolf, toiling away for years, chasing that singular, brilliant thread until a breakthrough unravels. It’s a powerful narrative, one that has fueled countless careers and, indeed, led to incredible discoveries. For generations, the path seemed clear: pick your patch of the vast scientific landscape, dig deep, become the undisputed expert, and let your work speak for itself. The R&D world was, in many ways, built on this foundation of profound specialization. And it worked, for a time.

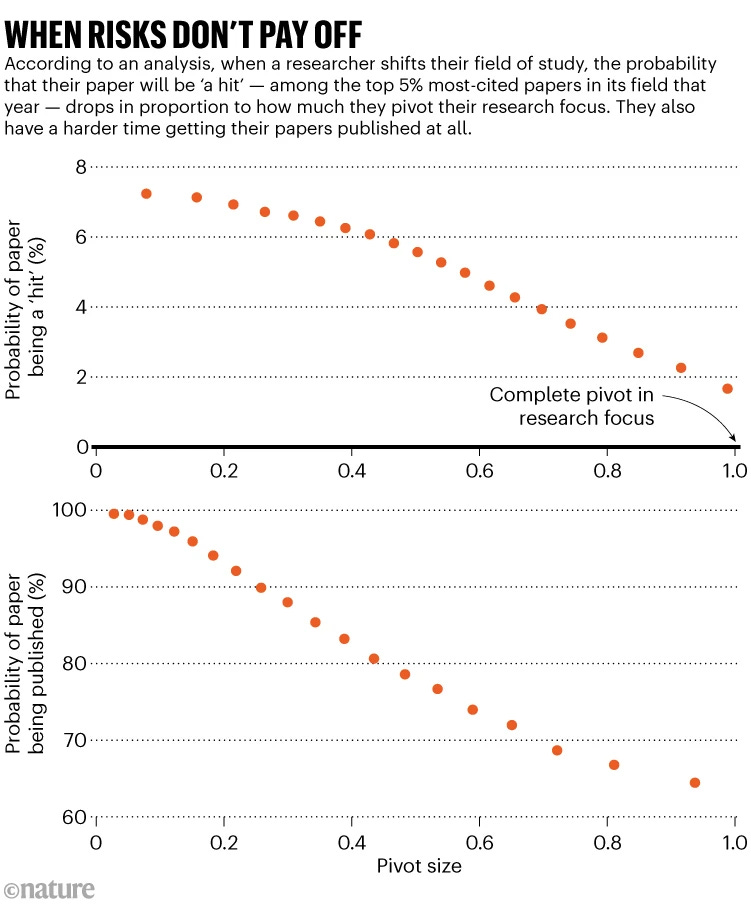

But a recent paper in Nature, bluntly titled "The pivot penalty in research," throws a fascinating, if somewhat unsettling, light on what happens when we stray from that well-trodden path. The researchers crunched an enormous amount of data, nearly 26 million papers and over a million patents. Their conclusion? When scientists or inventors "pivot," shifting their focus away from their core expertise, their new work often takes a hit. Fewer citations, a tougher road to publication, even less market enthusiasm for their patents. The further you leap, the harder the landing.

It’s a finding that, on some level, probably makes many of us nod in uncomfortable recognition. As the Nature news piece accompanying the study puts it, step outside your trusted circle, and that hard-won recognition can fade. Building deep expertise is the bedrock of good science, no doubt.

But here’s where my mind, as an environmental scientist and strategist constantly wrestling with the messy urgent problems of our world, starts to race. The challenges we face today, the ones that keep me up at night and hopefully fire you up too, are rarely neat, single-discipline affairs. Think about it: when I started my journey, the contaminants we chased often felt like individual culprits. We could isolate them, study their behavior within relatively defined chemical or engineering frameworks.

What about now? We're grappling with these sprawling, interconnected hydras. Imagine trying to tackle the PFAS, that are everywhere from our rainwater to our bloodstreams. This isn't just an environmental engineering puzzle. It’s a toxicological puzzle, a materials science challenge for new capture methods, a public health and policy knot, and it even demands we understand the social science of how communities perceive risk and demand action. These problems don’t politely wait for us to publish in our niche journals; they scream for us to reach across the laboratory aisles, to learn the languages of entirely different fields, and yes, to pivot.

The R&D landscape of the future, the one we’re already knee-deep in, doesn’t just value depth; it demands breadth and agility. The "endless frontier" now looks less like a series of parallel superhighways and more like a wildly dynamic ecosystem, where the most fertile ground, the most impactful solutions, often sprout at the messy, sometimes chaotic, intersections of disciplines.

The paper points out that high-pivot work, while often novel, can lack "conventionality" in the new field. It’s a crucial point. But I can’t help but wonder: are some of our most needed breakthroughs precisely those that seem unconventional to an established field, simply because they import a well-understood concept from a completely different domain? Think of the early days when AI was first being cautiously introduced to optimize complex chemical processes, or when biological principles started inspiring new materials. These were pivots, and they likely faced their own "penalties" before they became the new convention.

This isn't to dismiss the paper's findings. It’s a vital piece of work because it gives a name and a measure to something many have intuitively felt. But the conversation can't stop at just acknowledging the penalty. If we, as a scientific community, are serious about tackling the grand challenges like climate change, resource scarcity, emerging contaminants, global health, we need to ask ourselves some hard questions.

Are our funding structures, our tenure tracks, our very definitions of "impact" (often so heavily weighted on citations within a specific field) inadvertently building fences around the very interdisciplinary playgrounds where solutions are born? If the system penalizes the leap, how many brilliant minds will opt for the safer, more familiar shore, even when the burning questions lie across the water?

Perhaps the "pivot penalty" is a symptom of a system that hasn't quite caught up with the nature of the problems it needs to solve. What if, instead of a penalty, we reframed these courageous leaps? What if institutions actively created pathways for "supported pivots," pairing seasoned experts with those bringing fresh, if "unconventional," eyes from another domain? What if funding agencies explicitly rewarded the risk of interdisciplinary exploration, understanding that the impact might look different, might take longer to mature, but could be profoundly transformative?

The researchers who dare to pivot, to bridge the chasms between fields, aren't just changing their research trajectory; they're often the ones pushing the boundaries of what’s possible, connecting disparate dots to sketch out a new future. They are, in essence, the explorers charting the new R&D landscape. As Pasteur said, "chance favors only the prepared mind," but in a world of rapidly emerging threats and opportunities, perhaps true preparedness also lies in the courage to adapt, to learn, and to venture into the unknown, even if there's a toll at the gate.

The question for all of us, then, is how do we ensure that toll doesn't deter the journey? How do we build a scientific culture that not only tolerates but actively celebrates and supports the intellectual agility our future depends on?

Stay curious, stay critical, and maybe, just maybe, stay ready to pivot.

Moha.